Political editor

Getty Images

Getty ImagesScotland’s first minister John Swinney is not planning a party to celebrate his first anniversary in Holyrood’s top political office. That’s not really his style.

Instead of cake, balloons and fizzy wine he will mark this milestone by announcing an updated “programme for government” – as the countdown begins to the next Holyrood election in almost exactly a year’s time.

As Swinney told me at a recent news conference, this is not about tearing up his existing programme and starting again but building on what’s already there.

Four priorities

It’s an opportunity for him to show that his focus is on the day job rather than on dreams of independence.

You can expect him to talk a lot about his four stated priorities: improving public services, growing the economy, reducing child poverty and tackling climate change.

Swinney specifically wants to deliver noticeable improvements in the NHS over the next 12 months.

That’s not only because the public wants faster access to diagnosis and treatment but also because he believes cutting the queues is the best way to build trust with voters and to retain power.

He has also promised further economic action which in the short term could be about doing more to ease the cost of living pressures that many people feel.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn 7 May next year the public will pass judgement on what will by then be 19 years of the SNP in government in Scotland.

Voters will ultimately decide whether to keep John Swinney as first minister or kick him out.

The Conservatives, Labour and other opposition parties argue that the SNP’s record in office requires a change of political direction.

They highlight long waits in the health service, high levels of drug deaths and new ferries arriving years overdue and seriously overbudget.

Scottish Labour leader Anas Sarwar has said that if the SNP knew how to solve Scotland’s problems, they would have done it by now.

While Scottish Conservative leader Russell Findlay wants his party to be seen as a lower tax alternative to both the SNP and Labour.

Yet Swinney has greater cause for optimism about his political prospects now than he did a year ago.

There has been a remarkable shift in the Scottish political narrative since he replaced Humza Yousaf as first minister.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesYou may remember that Yousaf brought himself down by ending the SNP’s power-sharing deal with the Scottish Greens.

That set him up for a confidence vote that he no longer had sufficient support to win and he stood down as first minister.

Swinney’s inheritance was challenging.

His was a party fractured over independence strategy, gender politics and environmental commitments plus the legacy of harassment complaints against the former first minister Alex Salmond that were mishandled by the Scottish government.

Then there was the ongoing police investigation into the SNP’s finances which has since developed into a criminal prosecution of the party’s former chief executive Peter Murrell.

In July last year the SNP was heavily defeated by Labour in the UK general election but John Swinney, who had only just returned to the political frontline, escaped much of the blame.

It was not that his colleagues forgot that he had been at the heart of SNP government for most of the party’s time in office.

It was that many saw him as the only figure with the knowledge, experience and political clout to manage the aftermath of such a major meltdown.

Steadying the ship

Swinney was elected party leader unopposed in May last year and moved quickly to patch up some of the divisions within the SNP by appointing Kate Forbes to his cabinet as deputy first minister.

There have been other changes too.

He no longer has a minister for independence, has shelved plans to pilot juryless rape trials and the creation of a new national care service has been dropped in all but name.

Swinney has skilfully worked to calm controversy and steady the ship.

The UK Supreme Court’s decision on the definition of a woman under the Equality Act is another example.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe judges decided biological sex and not acquired gender was the answer.

Swinney immediately accepted the ruling as if it was a minor clarification of the law rather than a comprehensive defeat for the Scottish government by the campaign group For Women Scotland.

The Conservatives are determined that the fall-out from this legal battle at least merits an apology from the first minister to the women who took the case to court.

Instead, Swinney promises revised guidance on the provision and use of single-sex spaces and no attempt to revisit legislation to make it easier for trans people to legally change their gender.

He insists he will protect the rights of everyone in Scotland and hopes that will help him glide past this particular row.

The divisions in his party on this issue suggest his difficulties may not be so easily overcome, although the looming election may help bring different factions together.

Unifying figure

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHaving watched his old boss Nicola Sturgeon finish her term in office as a deeply polarising figure, John Swinney is attempting to avoid the same fate.

That is why he is recasting himself as a unifying figure – someone prepared to reach out across party lines to work with others to get things done.

Yes, this is the same John Swinney who played a central role in the independence referendum that literally made voters choose between “yes” and “no” on the question of leaving the UK political union.

To be fair, the first minister demonstrated a capacity for more inclusive politics during the Scottish budget process, making sufficient concessions to other parties so that only the Scottish Conservatives voted against.

He presented his recent “summit” with political, faith and civic leaders to counter anti-democratic forces in a similar light.

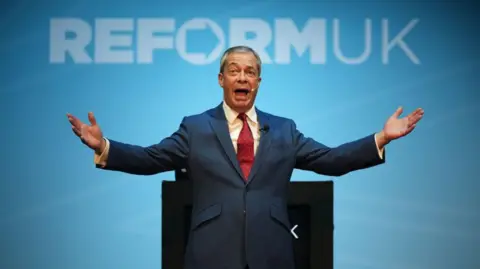

However, his main rivals think that event, which excluded Reform UK, elevated Nigel Farage’s party in the Scottish national debate.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesReform UK is persistently polling in double figures in Scotland and other pro-UK parties are worried.

While Swinney obviously despises Reform’s hostility to both immigration and the pursuit of net zero, he also knows they are more likely to take votes from the Conservatives and Labour than the SNP.

After Reform’s big gains in the English local elections on Thursday, there is a significant electoral test of their support in Scotland in just over a month.

The Hamilton, Larkhall and Stonehouse by-election on Thursday 5 June, following the death of SNP minister Christina McKelvie, will be widely seen as a two-horse race between the SNP and Labour.

This constituency vote has the capacity to entrench or overturn the prevailing narrative in Scottish politics – that Scottish Labour has lost momentum as a result of difficult decisions by the UK government on issues like welfare.

With a year to go, it looks perfectly possible that the SNP – far less popular than it has been in recent years – could still win a fifth term in office at Holyrood.

If the SNP can hold the Hamilton seat, their confidence will rise.

If Labour can take it from them, it will revive Anas Sarwar’s sense that the public mood is for further political change.

Labour thinks they can win if the vote is a referendum on SNP performance in devolved government but they fear that if it becomes a vote of confidence in Labour’s decision-making at UK level they will struggle.

The UK Labour government may have delivered record funding to the Scottish government but the SNP will not let the public forget the Treasury’s cuts to the winter fuel payment for pensioners, which Scottish ministers plan to mitigate.

Scottish Labour could do with the UK government using its economic clout to help address challenges in Scotland.

They were delighted by the prime minister’s promise of £200m to help secure a future for the Grangemouth industrial site but some in the party would like to see further intervention.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith the Hamilton by-election a month away, the Conservatives start as the third placed party.

They are worried that their new leader Russell Findlay has not had enough time to prevent Reform UK knocking them into fourth.

Whatever Reform’s performance, all parties will want to analyse what it might mean if replicated at the Holyrood election where the voting system is designed to make it easier for smaller parties to gain seats.

Without a Scottish leader, a policy programme or an established organisational structure, Reform UK claims to have 10,000 members in Scotland who have turned to them because they are so fed up with politics as usual.

One further twist is that when Nigel Farage turns up to campaign in the by-election he is likely to face detailed questions on recent comments where he suggested he was relaxed about John Swinney continuing in power.

That may make his brand of politics less acceptable to pro-UK voters even though independence has slipped down the political agenda and there seems little prospect of another referendum anytime soon.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFarage’s mission in Scotland he told the BBC is to gain a foothold at Holyrood, become part of the Scottish national conversation and then to replace the Conservatives.

That may help to explain why Russell Findlay is leaning more towards Reform UK positions in some policy areas.

For example, he recently called for a more affordable transition to a low carbon economy or what Reform calls “net stupid zero”.

This type of Tory tilt, designed to stop their traditional supporters switching to Reform, has already cost the party the defection of MSP Jamie Greene to the Liberal Democrats – a significant coup for their leader Alex Cole-Hamilton.

The Scottish Greens who gained significant profile during their period in government and will attract further attention when they elect a new co-leader to replace Patrick Harvie in the summer are among the range of other parties contesting the by-election and the Holyrood campaign in 2026.

Senior SNP figures tell me that independence will feature in their national campaign and ministers have promised one further paper completing their independence prospectus in the coming months.

That said, only the most optimistic independence supporter would predict another referendum in the next five years if there’s a “yes” majority at Holyrood after the 2026 election.

The issue is not dead but it certainly feels more dormant than at any time over the past decade.

The less that constitutional politics is to the fore, the more space there will be to discuss the competing offers from rival parties on the domestic issues over which Holyrood has control.

That’s health, education, law and order, parts of welfare, transport, the environment and some aspects of the economy.

Then there is global uncertainty.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPolitics at home is vulnerable to the impact of global issues, whether that’s import tariffs from the US President Donald Trump or the effects of conflicts in the Middle East, Ukraine or elsewhere.

Some of these issues may change the context in which domestic debates take place. Others could impact on the UK economy directly or as a knock-on effect.

The US president and his vice-president JD Vance have been known to speak up for their preferred candidates in other people’s elections.

That’s what John Swinney did when he suggested US voters back Donald Trump’s principal opponent Kamala Harris. Don’t be surprised if the Trump administration returns the compliment.

There’s no reason to think the first minister would lose sleep having President Trump against him or having Nigel Farage as a foil. Both could help motivate his political base.

No-one in Scottish politics can take anything for granted. A lot can change in a year and uncertainty is likely to be a hallmark of the campaign to come.

John Swinney and his rivals for the job of first minister are probably best advised to keep their fizzy wine on ice.