Environment correspondent, BBC Wales News

PA

PAThe UK’s climate change advisors have criticised the handling of a switch to greener steelmaking at the country’s largest plant in Port Talbot, which resulted in huge job losses.

Government ministers should have been better at planning ahead and making sure other green jobs were available locally, the experts said.

The independent Climate Change Committee (CCC) has set out its latest advice on how Wales reaches net zero – with a push for more electric vehicles, heat pumps and tree planting.

The Welsh and UK governments said they had been working together to develop “a strong vision” for the region’s future and deliver “our clean energy superpower mission”.

More than 2,000 jobs were lost at Tata’s Port Talbot steelworks following the closure of its blast furnaces in 2024.

The move brought an end to traditional steelmaking at the site, as the company grappled with losses of over £1m a day.

It was given a £500m grant by the UK government and is now investing £1.25bn to build a new electric arc furnace by 2027.

This will recycle scrap metal into new steel products, but requires far fewer workers on site.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe changes will have a dramatic impact on direct emissions of planet-warming gases from Wales.

The blast furnaces were constantly fed with coal, and their closure will have more than halved Wales’ industrial emissions since 2022, according to the CCC.

But environmentalists have warned the situation at Port Talbot could damage public support for climate action if it is seen to mean job losses and the demise of heavy industry.

In its report, the CCC said there were “important lessons to learn”, and that governments in both Westminster and Cardiff Bay should have been better prepared.

“The challenges facing the UK steel sector have been clear for many years and, given the significance of this site to the local economy, a more proactive and decisive transition plan should have been developed,” they argued.

The UK government should have taken steps to make industrial electricity prices more competitive, and convened “early and collaborative” negotiations between plant owners, workers and the community, the report said.

The Welsh government could have ensured “the right training and re-skilling programmes were in place well before closure”, it added, and developed a local industrial strategy to support alternative employment in areas like heating services and floating offshore wind.

The committee said Port Talbot’s experience should now be used “to guide future efforts to decarbonise other strategically and locally-significant emissions-intensive industries,” citing Pembroke’s oil refineries as an example.

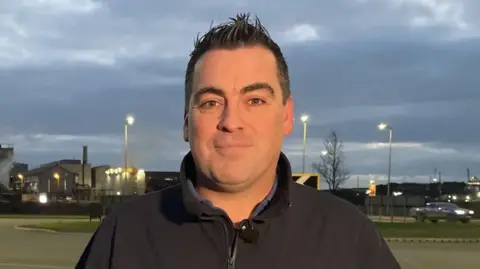

Former steelworker Shaun Spencer, who now works for a firm training electrical engineers, said he agreed with the committee’s comments “100%”.

He warned the feeling of “resentment and bitterness” was “very strong” among his former colleagues.

He added the approach had been detrimental to “everybody’s views of net zero” and to support for the way the UK and Welsh governments deal with things, “especially in this area”.

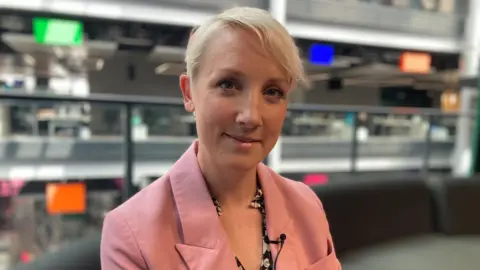

Emma Pinchbeck, the CCC’s chief executive, told BBC news what had happened at Port Talbot was “foreseeable and preventable”, and had “not been the best case study” for what a green transition should look like.

How can Wales reach net zero?

Like the UK, Wales has set a legally binding net zero target, which means that by 2050 it should no longer be adding to the total amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

The CCC provides independent advice on how much can be emitted over five-year periods, known as “carbon budgets”, and how each UK nation might achieve this.

Each carbon budget is a stepping stone to net zero, with the latest advice covering the period between 2031-35.

The report recommends a 73% reduction in average annual emissions over this period compared to how much Wales pumped into the atmosphere in 1990.

Emissions have decreased by 37% so far and the country met its first carbon budget between 2016-2020 mainly through changes to electricity generation – such as the closure of the last remaining coal-fired power station at Aberthaw in Vale of Glamorgan.

Future cuts will rely more on all of us making choices about how we live.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe CCC has made 16 “priority” recommendations for immediate action.

These include supporting people to better insulate their homes and install low-carbon heating systems, drive electric vehicles or opt for public transport.

By 2033 – in just eight years’ time – a third of cars and vans on Welsh roads should be electric, the committee said, and nearly a quarter of existing homes need a heat pump or similar technology.

‘Fewer sheep and cattle’

The committee also said the Welsh government will need to support farmers and rural communities to “diversify their income” away from livestock farming and towards woodland creation and peatland restoration.

In 2022, agriculture was the third-highest emitting sector in Wales, accounting for 16% of Wales’ emissions.

Cattle and sheep numbers should fall by 19% by 2033 due to changes in agricultural policy but also a shift in diets with less meat and dairy consumed UK-wide, the report has predicted.

The proportion of woodland cover across Wales will rise from 15% to 17% in 2033 and 26% by 2050, according to the committee’s projections.

Farming union NFU Cymru said the Welsh government needed to “reflect and consider” whether that advice fit “with the circumstances we have in Wales”.

“Many thousands of people rely on agriculture and livestock production,” said the union’s president Aled Jones.

The Welsh government thanked the CCC for the report which it said it would now “review and use to set Carbon Budget 4 in regulation before the end of the year”.

A spokesman said it had been working with the UK government, the local authority and key stakeholders as part of the Tata Steel UK transition board to support affected individuals and businesses and develop a “strong vision for the future of the region”.

It hoped do this by “making the most of” opportunities from new infrastructure and investment in areas such as renewable energy, he added.

The UK government said it had committed £2.5bn “to rebuild the steel industry for decades to come as it decarbonises”.

“Decarbonisation should not mean deindustrialisation and we will ensure a bright and sustainable future for UK steelmaking,” a spokesman added.

“We will work with the Welsh government as we deliver our clean energy superpower mission and accelerate to net zero, growing our economy and making working people better off.”